Dear General de Gaulle ...

Tracing the mystery of a West Virginia nun's letter to a world icon | Jan. 24, 2023

By Douglas John Imbrogno | TheStoryIsTheThing.com | January 24.2023

The World Wide Web is a Weird place. It’s absorbing and maddening — as in, making us angry, if not literally mad — plus, so endorphin-intoxicating as to suck up all the extra time we might otherwise devote to our long-delayed Life’s Work. But, then, you get an email like the one I got this week in my digital in-box. And all is forgiven.

Sent from Glasgow, Scotland, the e-mail said simply:

An item on ebay.uk that may be of passing interest to you.

General de Gaulle’s office to the sister.

R Walker

Caledonian Philatelic Society

De Gaulle? Caledonian Philatelic Society? E-bay in the U.K.? What sister? Huh!? And ‘philatelic,’ isn’t that stamp collecting? I asked my friend Merriam-Webster for help: “The collection and study of postage stamps, postmarks, and related materials.’ Attached to the email was a letter written in 1965, sent the last day of the year from Paris by an aide in the office of Charles de Gaulle, the renowned World War II French Resistance leader and, by then, as the letterhead notes, ‘La President de la Republique’ of France.

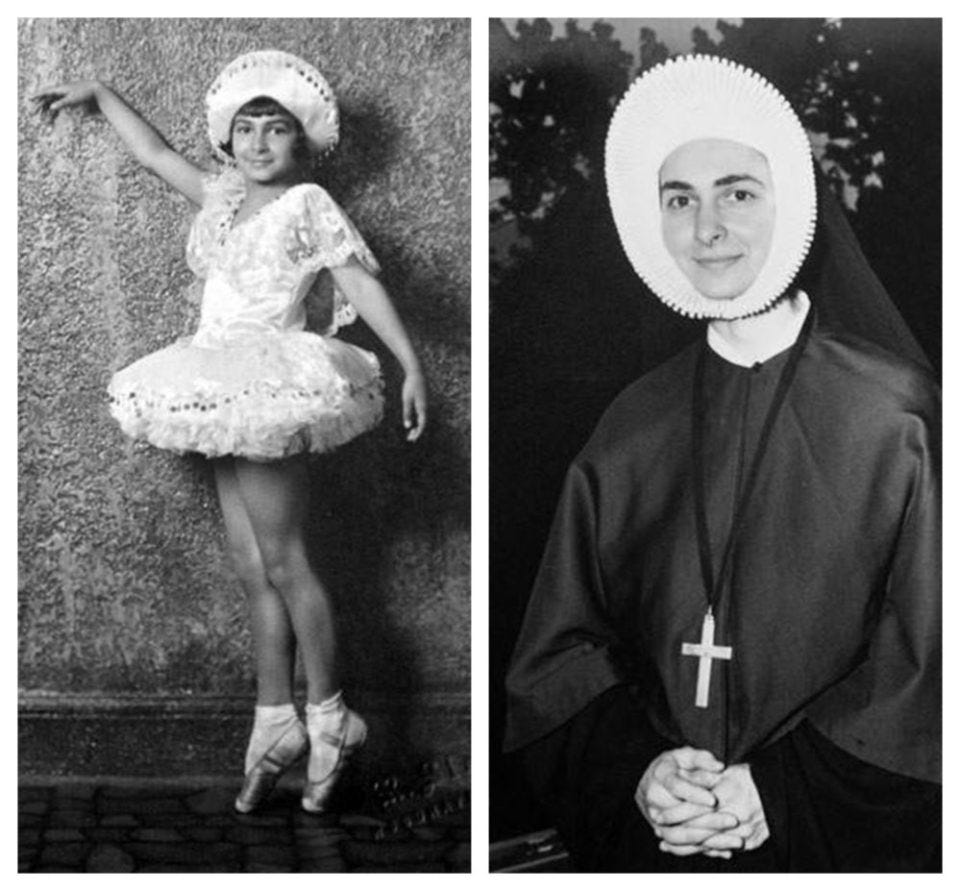

The letter was addressed to ‘Reverende Mere Mary Pellicane’ at the Convent of Our Lady of the Retreat in the Cenacle,’ a cloistered nunnery at Lake Ronkonkoma, New York. And, then, it all became clear. Sort of. For Sister Mary Pellicane, a feisty Catholic nun and fellow Italian, had been a friend of mine for many years. I had made her the subject of two profiles and a podcast while working at The Charleston Gazette in West Virginia’s capital city. That was before she passed away at the august age of 99, on March 17, 2021, while a long-time resident of the West Virginia Institute for Spirituality in Charleston, which she co-founded.

Yet, the curiosity of the letter remained. Using my kindergarten-level French and an online translator (help me out here, better French speakers than I if I muck this up), the letter approximately reads:

My Reverend Mother: General de Gaulle has well received your letter. In regards to your testimony to him, Monsieur the President of the Republic has charged me with expressing his thanks. Please accept, my Reverend Mother, this expression of my respectful sentiments.

OK. Sure. Cool. But what had Sister Pellicane written to the great general? A fan letter? A critique of his running of France? A remembrance of her own, sometimes painful engagement with World War II, as a pre-cloistered, raven-haired daughter of Sicilian immigrants?

I wrote back to my correspondent at the Caledonian Philatelic Society. Essentially, saying: ‘What can you tell me about this? What gives?’ Russ Walker wrote back, filling in what details he knew about the letter. Which was for sale. On eBay.

In the U.K.

Doug: It is on sale by a dealer that I buy from quite often — he has some more unusual French wartime material that is often of interest to me. As the recipient’s name was less usual, I did an internet check and came across your website with so much of this lady’s history. I also

discovered, of course, that sadly she died a few years back. It always strikes me how so many of these collectable items travel around – why is this lady’s letter from de Gaulle now in London? Another mystery! The letter suggests that she was expressing admiration for de Gaulle. Glad this was of interest and I hope this adds a wee bit to her story.

All best wishes

OK. Sure. But, then, I thought:

Mystery only somewhat solved!

Mary Pellicane was born in 1922, to a Sicilian immigrant couple who initially settled into a cold-water Brooklyn flat. (By the time little Mary came along, they had warm water). The family later moved to Queens, 10 minutes away, as the 20th century began to work its changes on family life.

“We got a telephone, and that was thrilling,” Sister Pellicane recalled in my 2016 profile “NOT A SOUND: 70 Years a Nun”, marking seven decades in her order of nuns. “When you had a long distance call between Brooklyn and Queens, there was a very long ring and they said, ‘Keep quiet!’ And the people would get on the phone and shout from Brooklyn to Queens!”

Wishing to raise children acclimated to American culture, her parents sent young Mary off to ballroom dance lessons. Here is how she recalled it: “My dad wanted us to be proper Americans. My brother Joe and I were sent to a ballroom dancing school. When I was in college we danced a lot. That was the only entertainment you had.”

The profile goes on to note:

Mary grew up into an inquisitive, cultured young woman, eventually majoring in French with a minor in Spanish. At age 21, She took a job as an expediter at the General Electric Supply Co., in Greenwich Village, earning the grand sum of $17 a week.

World War II came along and emptied the city and country of its young men. Before they left for war, they asked many a young woman for their hand in marriage before shipping out. Mary was among them. She’d been seeing two guys.

“One came to my office one day and said: ‘We have to get married right away!’ I said ‘Why?’ He said: ‘I’m being shipped overseas.’”

Mary stood her ground. She answered: “I didn’t say I would or would not marry you and if I did it wouldn’t be right away.’” …

But what Mary was telling herself as the young serviceman proposed to her was: ‘What would happen if he didn’t come back? I can’t be the mother of a fatherless child.‘

World War II inflicted its tragedies not only at a macro level — see how a younger Charles de Gaulle united the Free French resistance movement against the Germans — but at an intimately personal level back home. Mary’s young soldier suitor, she came to learn a short while later, had been shot down and died overseas.

By then, the seeds of her future life had been planted, after an initial visit at age 22 to Our Lady of the Retreat in the Cenacle, a semi-cloistered congregation of nuns on Long Island. She went that first time to accompany a friend who was heartbroken at the loss of her husband and felt the need for a spiritual retreat from society. Mary had no thought of donning the cowl worn by the nuns, even while returning now and again, afterwards, to the center for a spiritual tune-up.

“I would go whenever I was able to go for a day or two of prayer. But I still wasn’t thinking religious life. I was thinking it was a wonderful place. But I was also still in touch with a couple guys I had gone with in college. I was two-timing.”

For updates on new poems, essays, diatribes, experimental videos & sorta memoir excerpts, subscribe to this site’s free e-mail newsletter: TheStoryIsTheThing.substack.com

By 24, the lure of the peace and solitude, the quiet life of a cloistered nun, drew her into its fold.

“As we went into the chapel, the nuns used to chant in Latin about five times day,” she recalled. “And the rhythm. Everybody dressed the same and all were very reverently bowing. Around the grounds, you would see people walking silently and maybe saying the rosary. It was just a sense of harmony for me.”

She took the plunge and joined the order, taking a vow of silence. It was all against the wishes of her parents. Her father was so upset that he refused to accompany his daughter to the convent the day Mary became Sister Mary. Her mother came, but crying, while her brother Bob drove her there.

“My parents were very opposed to my going to convent, especially a cloistered convent,” she recalled.

The rules of the order were such that she was not offered the chance to leave to attend Bob’s funeral after the former World War II troop transport pilot died flying a plane in the reserves after the war. Here is how she described what happened:

She was then a cloistered nun, her face encircled by a ridged snow-white coif like some exotic bird, her head topped with a black cowl and dressed in thick surge black robes. She was not offered the chance to leave to attend her younger brother’s funeral.

“My father said that was the worst thing, almost as bad as his dying, that I couldn’t go to the funeral. If I had been bolder — which I was not — I could have pressed it. They made exceptions, but not frequently. And no one offered it to me. So I didn’t go.”

She got bolder. I urge anyone interested in reading my fuller portrait of her life — I used the word ‘feisty‘ above and it remains the best one to describe her — to click this link (read all the way down to the profile) or tap the graphic of her below this article. None of what I have written here or there, however, will solve the mystery of what exactly Sister Pellicane wrote to Monsieur the President of the Republic, Charles de Gaulle.

But, let’s do the math. She sent the letter in 1965. She was, by then, a seasoned nun at the age of 43, or so. She had certainly, by that time, grown out of her cowled, wallflower, novice nun stage. So, as you get to know her a bit more from my profiles and podcast interview — which detail her cranky, outspoken gun-control letters-to-the-editor, her frontline work with generations of alcoholics as a 12-Step sponsor, her wisdom accrued in both deep silence and worldly conversation — it could well be anything that she wrote to the General.

As to the physical letter itself being offered for sale, I have no interest in purchasing it or its admittedly cool stamp (which depicts the Chateau de Joux, a fortress near the Swiss border resonant in the history of France and military architecture for one thousand years).

After Sister Pellicane died, Sister Carole Riley, executive director at the Institute for Spirituality, who considered her elder sister a mentor (and who, she says, “saw goodness everywhere”), invited a handful of those of us close to her to retrieve a memento from among the small body of possessions in her living quarters. While visiting the sister one day late in her long life, when she had mostly taken to her bed on the institute’s second floor, she pointed at a 6-inch-high porcelain statue of a cowled nun on a nearby shelf. The statue looked remarkably like the young novice nun christened Sister Mary Pellicane so many decades ago.

The sister nodded to the statue from her bed.

“She keeps me honest when I get out of hand,” she said.

Now, the Sister statue, standing upright beside a seated Buddha on my meditation shelf, tries to keep me honest.

You totally captured her spirit!! I can only imagine her throwing her head back in laughter as you so eloquently penned yet another mystery of this “sage”! Thank you Doug!!!

Since the adventurous Sister Pellicane seems to have been very much of her time, I rather doubt she was reaching back to WWII with General de Gaulle. He had been in D.C. for JFK's funeral hardly more than two years before this letter was sent, U.S. action was heating up on turf France had recently vacated in Vietnam, and Paris was making mischief in francophone Canada. If not advising "Monsieur the President of the Republic" on matters of state, she may simply have sent him holiday greetings. His note after all is postmarked 30 December.